An ode to histotechnology

When people look at da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, they are mesmerized. They ask themselves “how did he do it?” There is something about her smile that everyone writes about and wonders, “how did he do it and what does it mean.

If you look up “Mona Lisa Smile” on Google, you will find 1,320,000 hits in less than one second. One article is titled Mystery of Mona Lisa’s smile “solved” as experts….

So real art captures the eye’s attention and it leads to all sorts of appreciation. Masterful art has meaning to the observer. How we react is an individual matter. Most people want to study the works more closely and deeper in many cases.

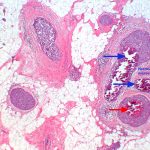

Much in the same way, a pathologist early in his/her career learns to appreciate a well stained histology slide. Literally in the back of the lab, histotechs labor to create works of art each day. And these techs are dealing with only a blue and red-orange color stain. You might ask yourself, “how do the histotechs create such works of art.”

Only a few hundred years ago, the Renaissance painters only had eight colors to work with and created masterpieces. Today’s painters have thousands of colors to use to create unforgettable works. Yet the unsung histotech works with only two stains to create, in their world of endeavor, masterpieces.

So, let’s talk about the art of histopathology. How do the histotechs create masterpieces? There is more to the process than meets the eye—quite literally.

INITIAL HANDLING OF THE TISSUE:

The tissue to be examined microscopically needs to bathe in formaldehyde for six hours or more before processing begins. This solution stops all degradation of cellular processes and keeps the tissue in as natural a state as possible. Distortion is minimal.

OVERNIGHT PROCESSING:

Overnight processing automatically places the selected tissue in a series of chemicals that include:

- Formaldehyde

- Alcohols,

- Xylenes and finally

- molten paraffin.

CUTTING THE PARAFFIN BLOCKS:

Each piece of tissue that has processed overnight is placed in a small mold and molten paraffin is poured over the piece, to form a paraffin block after the

paraffin has cooled. The blocks are placed on a microtome with a razor-sharp blade, one at a time, and thin slices are cut from 2-10 microns depending on the tissue type. These slices are so thin you can see through them. Cutting is critical to make sure there are no wrinkles or tears in the tissue itself. These thin slices are placed on a glass slide via floating them on a warm water bath. Staining comes next.

STAINING OF THE TISSUE SLICES:

As mentioned above, the histotech only has two color stains to work with. Hematoxylin stains the cell’s nucleus a dark blue. The eosin stains the cell cytoplasm and stroma between the cells mostly a reddish color with many hues possible.

THE PATHOLOGIST

It cannot be emphasized enough that the pathologist heavily relies on the perfection of the histologist tech’s working artistic miracles. And we rely on it being done every day. We can be literally a brilliant pathologist, but if we are handed poor quality histology slides, our abilities become more limited.

PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED:

With close to 40 years of looking at slides, there multiple reasons for less than perfect histology slides. A partial list is compiled below:

1. Sample did not bathe in formaldehyde long enough

2. Sample has undergone desiccation

3. Pathologist/PA cuts samples that are too big to be submitted, which prohibits complete penetration of formaldehyde and subsequent chemicals

4. Something happens to overnight processing—machine fails

5. Solutions in processing machine need constant refreshing

6. Critical embedding technics when placing tissue in paraffin block

7. Cutting paraffin block slides with no wrinkles or tears

8. Staining area must always have fresh solutions and stains

9. Tissue contains calcifications

10. Using a microtome that is not well maintained or of good quality

11. Proper work environment: a room that is not too cold, hot, humid or drafty. Static electricity can ruin a histotech’s day causing sections to “fly away” or stick to clothing, or the microtome can become unmanageable.

All of the above processes and problems must be constantly monitored by the histology staff. If volumes are high, sometimes solutions and stains must be changed more often, sometimes multiple times a day.

Pathologists are people for the most part who love their microscope. It is the tool that creates their reputations. Pathologists are lucky when they receive compliments from clinicians, bragging on the excellence of a recent diagnosis. It is a time when the pathologist can relish the pat on the back or the “Atta boy or Atta girl” remark. But how often does the pathologist remember the da Vinci (s) who is (are) the back lab turning out masterpieces and doing so with hardly any recognition?

So, this pathologist tips his hat to those histotechs over the past nearly 40 years who have endeavored to turn out beautiful masterpieces on 3 x 1 inch glass slides. I salute all of you!

In a few words, like the Mona Lisa, what is the pathologist looking for in a histology masterpiece? 1. Clarity, where the nuclear details are distinct from the cellular cytoplasm; 2. Color, saturated staining so that cells and other tissue elements stand out separately; 3. Pop, is related to #1 and 2, and it reflects a perfectly cut and stained slide, that has almost three-dimensional qualities. For an old pathologist, those three qualities found on a histology slide makes me smile, kind of like the Mona Lisa.

Below is a histology slide photograph of low grade breast invasive ductal carcinoma. It has all three features outlined above.

Thanks to Stephanie Huff, BS, HTL (ASCP), Pathology Department Manager at Houston Northwest Medical Center, who made sure the technical information was accurate and correct.